Indigenous employment in Australian agriculture

)

Abstract

Despite the growing demand for an agricultural workforce in Australia, Indigenous peoples are underemployed across the sector, representing just 1.8% of the current agricultural workforce (Slatter, 2023) and 2.1% of the workforce with the inclusion of aquaculture, forestry and logging and agricultural support services. The Indigenous workforce of approximately 6,000 peoples is a significant decline from previous decades, when Indigenous peoples were relied upon to develop stations and grow the agricultural industry. First Nations peoples provide a significant opportunity to address current and future agricultural workforce demands, particularly to align with social licence pressure on the sector. Reconciliation Action Plans, university scholarships and better retention and promotion of Indigenous employees provide significant opportunity to build pipelines for Indigenous talent, while reducing unemployment rates of First Nations peoples and creating pathways for ongoing connection to country.

Introduction

As the agriculture industry aspires towards the goal of $100 billion gross value of production (GVP), workforce concerns remain at large for much of the sector. Despite significant interests in land, equating to over half of Australia’s landscape, the total production value derived from the Indigenous estate is less than 50% of GVP revenue (Barnett et al., 2022). Concerningly, the majority of revenue generated from the Indigenous estate provides no benefit to Indigenous peoples. The employment of Indigenous peoples in agriculture is built on a history of tension, exacerbated by the contestation for land, facilitation of slavery and the ill-treatment of First Nations employees (Bunbury, 2002).

Despite this, growing literature notes the need to diversify the agricultural workforce, including building a First Nations talent pipeline and supporting existing Indigenous employees (Pratley et al., 2022; KPMG, 2023). As the demand for agricultural employees continues to increase (Pratley et al., 2022), First Nations talent provides a unique opportunity to enhance cultural, environmental and social outcomes for agriculture while also assisting the Federal Government’s national strategy to increase Indigenous employment (among other social determinants) under ‘Closing the Gap’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021).

This paper explores the background relating to agriculture and the First Nations workforce, the current state of Indigenous employment in the sector, opportunities for engaging Indigenous talent and concludes by considering industry action that needs to occur.

Background

The Australian agriculture sector long relied on the labour of Indigenous men, women and children until the implementation of the equal wages decision in the late 1960s (Bunbury, 2002). This reliance was surrounded by strong decisions of both self-determined and forced integration into Western agricultural systems, with cases of unpaid wages, mistreatment and massacres demonstrating the plight of the relationships (Bunbury, 2002). Recorded conditions from Indigenous workers include “(a)ll the work on the station was done by the Aborigine… young and old alike were beaten and kicked ‘to make them work harder’” (Host and Milroy, 2001). Another example noted that stations “were built on black labour. On sour bread, damper, roo meat and whippings” (Host and Milroy, 2001).

Positively, instances of ‘co-existence’ have demonstrated a connection between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, with the triumphs of Indigenous stockmen, for instance, reflected in rodeos and folklore (for example, Davis, 2006). The historic relationships and experiences of Indigenous peoples with Western agriculture vary across the country, with each requiring a detailed understanding.

The reliance upon Indigenous peoples was pertinent for building Western agricultural landscapes, with some farm managers noting that the “greatest trouble and complaint was the scarcity of blacks upon the run” (Foster, 2000). This is further depicted by an increasing inclusion of First Nations labourers, with states such as Western Australia having fivefold increases in Aboriginal labourers between 1881 to 1901, recording up to 12,000 peoples at the turn of the century (Host and Milroy, 2001).

The ‘employment’ of Indigenous peoples provided some First Nations people with the option to stay on country, providing the ability, and the expectation, to continue traditional agriculture to enhance rations (Foster, 2000) and engage in cultural practices alongside seasonal work (Paterson, 2005). Equally, Indigenous peoples noted the importance of cattle industries, for example, to their own lives, with some engaging in their own ventures within a generation of colonisation (Paterson, 2005).

It is important to note that there is great difficulty in quantifying the historic contribution of Indigenous workers and participation in the agricultural sector, challenged by the lack of data, racist definitions and societal attitudes towards what it meant to be ‘Aboriginal’, and the lack of reporting by pastoral stations to governments (Head, 2000). This is best demonstrated by the current Minister for Indigenous Australians, the Hon. Linda Burney MP, who noted:

The Indigenous workforce was often the bottom rung within agricultural ventures, replaced by convicts and ex-convict labour in Perth and during later years, machinery advances across the country (Host and Milroy, 2001). Indigenous activism and campaigning for better working conditions and equal wages also resulted in tensions. The tensions led to friction, resulting in the active lobbying by the agricultural sector creating provisions in the awards against Indigenous equal wages, tarnishing Aboriginal workers as “slow workers” to enable reduced payments (Bunbury, 2002). Further actions by agriculture included public attacks, with commentary by the Cattleman’s Association of North Australia categorising Aboriginal workers as “Lazy” (Stead and Altman, 2019). The success of the radical racialisation of Indigenous workers led to a mass removal of Aboriginal peoples following the equal wages implementation in the 1970s (Bunbury, 2002).

The Present

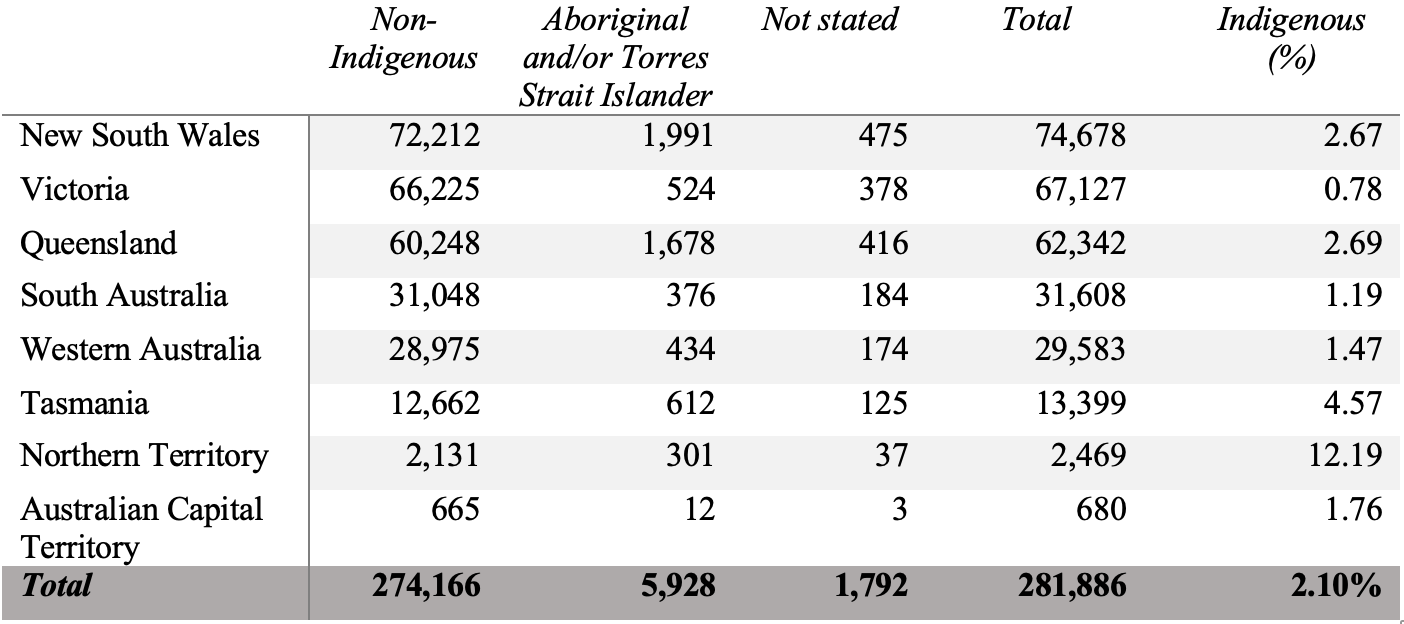

Despite the complicated history and the perceptions of Indigenous peoples against current agricultural systems, particularly regarding native title, First Nations peoples remain an important opportunity for the sector. Approximately 5,900 First Nations people were reported (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023) as being employed in the agricultural industries in 2021, with 2.1% of the broader agricultural workforce identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (as depicted in Table 1), an increase of 1,300 or 28.2% from 2016 (Barnett et al., 2022). This brings the agricultural sector’s Indigenous representation in line with other industries, although there is more work to be done.

The National Farmers Federation highlights the importance of Indigenous opportunities in their 2030 Roadmap (National Farmers Federation, 2019) including industry leadership and “better representation of indigenous (sic) agriculture”. However, despite the attention of Indigenous engagement, the related metric for measuring working with Indigenous peoples is whether gender parity is achieved (National Farmers Federation, 2019).

There is significant distribution of Indigenous people across the States, with concerning trends in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia as underrepresented cohorts, compared with over-represented proportions in Northern Territory and Tasmania, when compared with national data. It is important to note that while some recent trends show small positive improvement, Western Australia, for example, depicts a decline from 12,000 to 434 since 1901. The question remains as to why this decline is so extreme relative to other states.

- Table 1. Distribution of non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples in the agricultural, fisheries and forestry sector (on-farm) per State based on 2021 Australian census (source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023).

The lack of consistent data remains as a key concern when quantifying Indigenous involvement in the agricultural sector. Often, Indigenous representation as part of the agricultural workforce is quoted as 1% (see, for example, Binks et al (2018); Barnett et al., 2022; KPMG, 2023), which demonstrates the challenges of inconsistent data sources and need for further data capture by the sector. There is also a variance in reporting between agriculture and the inclusion of fisheries and forestry, with Slatter (2023) reporting Indigenous engagement in agriculture at 1.8%. There is a need to extend employment understanding beyond the farm gate, to workplace data in agribusiness more broadly.

Concerning is the long-standing typecasting of roles Indigenous peoples hold within agriculture, often depicted as cheap labourers (Anthony, 2004). Noting this, First Nations Australians are almost twice as likely as non-First Nations people to be employed as labourers in the current agricultural workforce (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021).

There is also the general reluctance for Indigenous people identifying in the workforce or in Government documentation, despite a desire to do so (Brown et al., 2020). Reasons include racism, particularly appearance racism, added load placed on Indigenous employees (known as cultural load) and identity strain, whereby the person’s identity does not meet the norms or expectations of dominant workplaces (Brown et al., 2020).

Demand for agriculture workforce

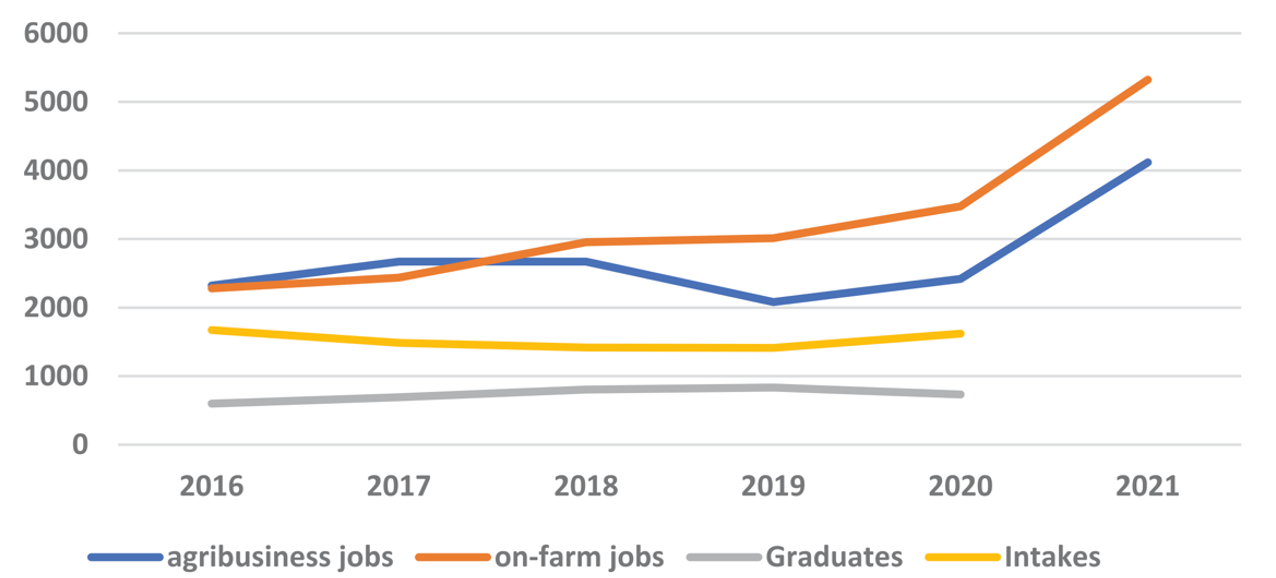

In a period of low unemployment as currently experienced, the agricultural sector faces distinct challenges in attracting a suitable workforce, with a growing trend of both on-farm and off-farm employment opportunities (Figure 1, Pratley et al., 2022). The challenges for attracting and retaining staff will further intensify, exacerbated by an ageing workforce, intense competition from other sectors of the economy for workforce and the potential risks in our reliance of international workers, as exposed during Covid 19.

Figure 1. Discrepancy between job availability and the supply of qualified people in agriculture coming out of universities, 2016-2021 (Pratley et al., 2022)

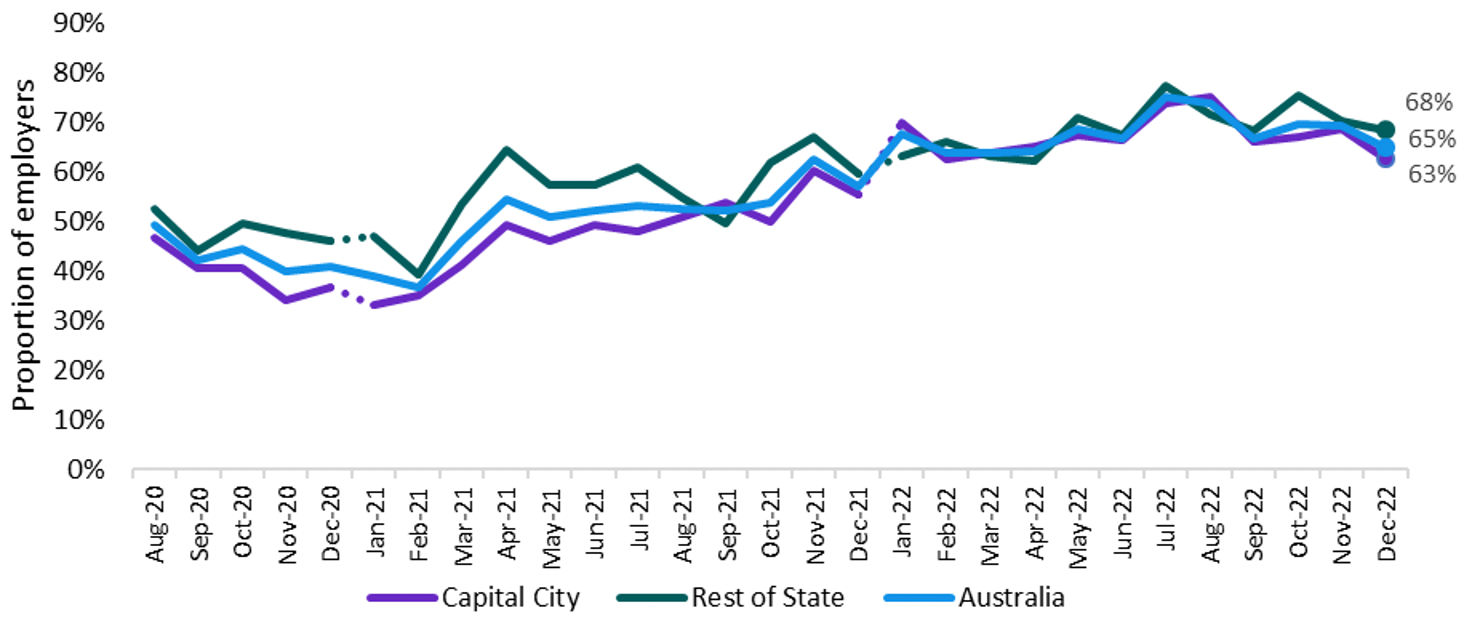

This is further demonstrated by analysing the Australian recruitment difficulty trends, depicted in Figure 2 (Jobs and Skills Australia, 2023). The recruitment difficulty rate in December 2022 was 65%, 26 percentage points above the level recorded in January 2021 (39%). This upward trend in recruitment difficulty has occurred across higher skilled, lower skilled, casual and non-casual vacancies and therefore is a cause for concern in the agriculture sector where job availability has outstripped availability of qualified personnel.

Figure 2. Recruitment difficulty, August 2020 to December 2022 (Jobs and Skills Australia, 2023)

Recruitment methods, used by the employers in Figure 2, also present difficulties in quantifying the number of agricultural jobs, with a reliance in the use of social media and word of mouth increasing with remoteness (Jobs and Skills Australia, 2023). In regional areas, for example, it is reported that 36% of employers used social media and 34% used word of mouth to attract workers (Jobs and Skills Australia, 2023). Significantly, social media and broader agricultural media often fail to depict Indigenous involvement in the sector and therefore it is unlikely for First Nations peoples to see themselves in the industry or picture themselves being recruited - you can’t be what you can’t see.

The imbalance between supply and demand for workforce provides opportunity for potential Indigenous employees. It is also opportune as all industries are expected to work towards workforce parity of 3.8% (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). In agriculture, current Indigenous employment is just 2.1% on-farm (as shown in Table 1) and therefore Indigenous employment will need to increase significantly to meet the workforce parity in terms of current workforce demographics on farm and in off-farm agribusiness. As businesses implement reconciliation action plans (RAPs) to further their social licence alongside company strategic plans, further attention to Indigenous employment will become a critical focus.

There is also often geographical alignment between where Indigenous peoples live and the demand for employment, with the majority of agriculture, fishing and aquaculture primary production assets being located in rural, regional and remote Australia where 65% of First Nation peoples reside (Barnett et al., 2022).

Supply of Indigenous workforce

Despite significant opportunities for Indigenous employment, there remains supply constraints of First Nations talent.

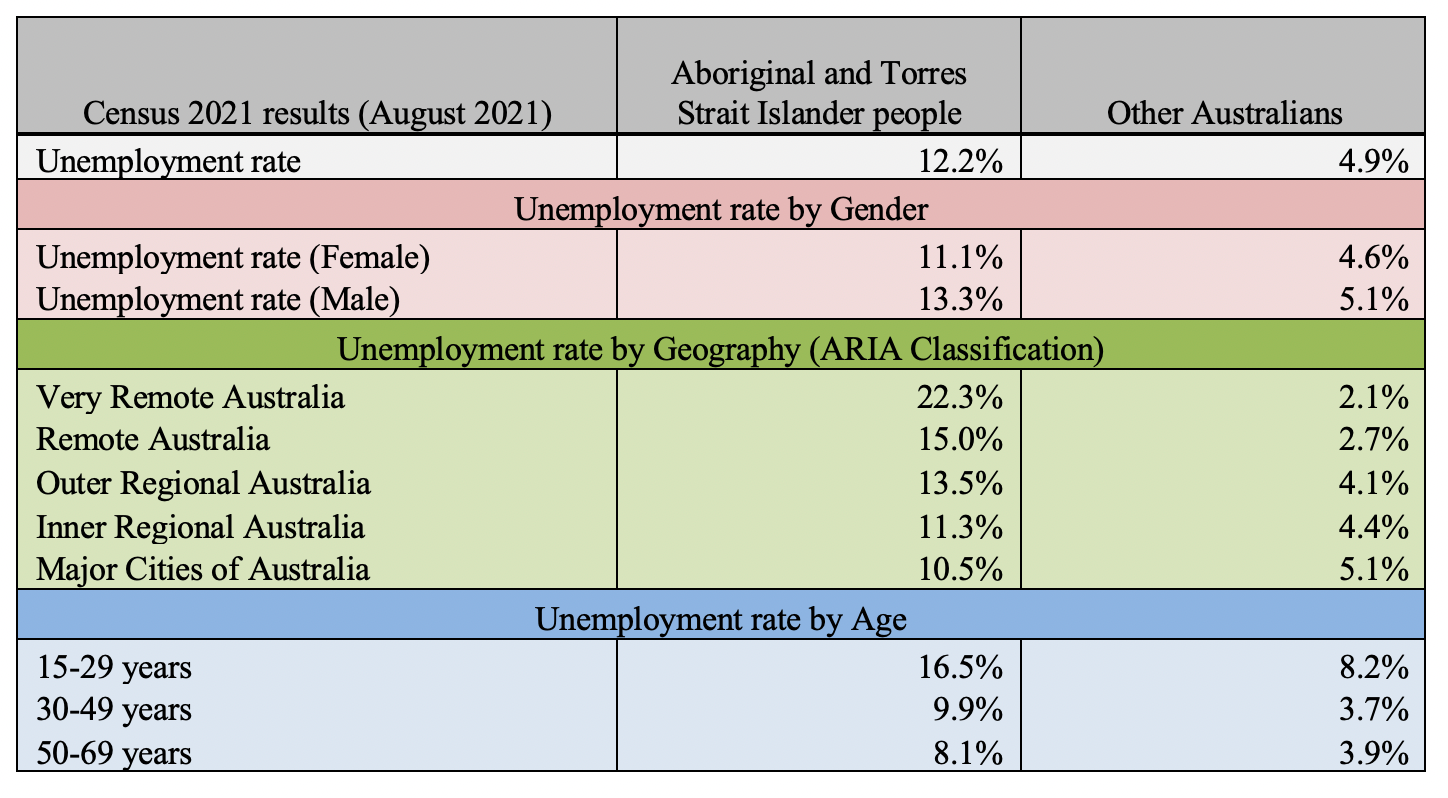

As depicted in Table 2, Indigenous peoples experience high unemployment (12.2% compared with 4.9% of the remainder of the population). First Nations people also have an inverse relationship in terms of the unemployment rate by geography relative to ‘Other Australians’, with the highest rates shown in Very Remote Australia and Remote Australia, compared with Inner Regional Australia and Major Cities for non-Indigenous Australians. Table 2 also shows that there are significant opportunities for agriculture to engage with Indigenous peoples aged 15-49 as an immediate pipeline, as unemployment in these age groups is double that of ‘Other Australians’. Adding value with education and training provides a significant opportunity across all agricultural roles.

Table 2: Unemployment rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in comparison with ‘Other Australians’ (Personal correspondence, Dr Siddharth Shirodkar)

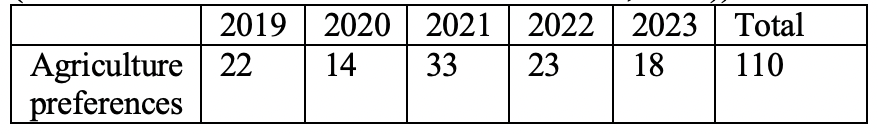

Universities present an opportunity for further engagement, noting the increased demand for agribusiness professionals. Currently, Indigenous university graduates represent a cohort of fewer than 5 graduates each year across all universities in Australia (Pratley, 2019). In NSW, for example, there is a decreasing trend of Indigenous students attaining academic rankings to apply for university, falling from 1,138 in 2020 to 843 in 2022 (University Statistics, 2022). This is also reflected in students choosing agriculture as a preference at university, demonstrated below in Table 3, with just 110 Indigenous students preferencing agricultural courses in NSW in the past 5 years (Universities Admission Centre NSW, 2023).

Table 3: Indigenous applicants preferencing an agriculture course at university for the years 2019 to 2023 (Source: Universities Admission Centre NSW, 2023).

Opportunities to build First Nations agriculture pipeline

It is important therefore to explore potential pathways to attract and retain First Nations personnel within the agricultural sector. The following present options.

Supporting the existing Indigenous workforce Workforce conditions require considerable attention to ensure cultural safety for Indigenous employees (Brown et al., 2020). Despite strong data noting the importance of Indigenous peoples identifying publicly in the workplace, the outcomes for such employees often are an increased cultural load and/or racism (Brown et al., 2020). This can impact on employee retention, with Indigenous employees who have experienced racism being two times more likely to look for a new employer in the next year (Brown et al., 2020).

Support for Indigenous employees can take many forms, from increasing the cultural capability of the workforce more generally to decreasing the reliance (cultural load) upon First Nations staff for Indigenous events and connections. While standard cultural awareness training provides an important training opportunity for staff, the complex relationships between First Nations peoples and agriculture need to be explored with specificity, given the specific involvement and tensions of historic and current agricultural policies (Bunbury, 2002).

Media and promotion Following the mantra that you can’t be what you can’t see (as explored in Pratley et al., 2022), there is also opportunity for the agricultural sector to improve its portrayal and promotion of Indigenous employees and their career prospects. Currently, there is a lack of visual materials that portray their belonging and connection to current agricultural systems. For instance, the NFF report on Indigenous engagement (KPMG, 2023) is covered by a picture of cattle, rather than Indigenous peoples.

Mainstream agricultural media and agribusiness organisations are yet to promote any stories of Indigenous success, complicated further by the lack of opportunities for First Nations peoples to identify in their systems, or at work. Equally, universities and employment programs need to show diversity across their recruitment materials to represent this connection, thereby encouraging Indigenous peoples into the sector.

University Scholarships The lack of Indigenous university students is a significant concern, with low attraction and retention rates. While many universities offer a range of Indigenous scholarships, Charles Sturt University at Wagga Wagga, NSW has developed a specific Indigenous Agricultural Initiative to provide scholarships for Indigenous students studying agriculture at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels (Charles Sturt University, 2023).

Equally, agriculture needs to develop pathways from within schools into the sector and from universities into the workplace. It is likely graduate programs, for example, will be developed in line with Reconciliation Action Plans and will provide initial pathways for these roles.

Reconciliation Action Plans Reconciliation Action Plans (RAPs) provide an opportunity for organisations strategically to consider their role as a business in advancing reconciliation. Over 2,200 organisations have developed a formal RAP over the past 17 years (Reconciliation Australia, 2022), with agricultural businesses a laggard in terms of their commitment. A RAP provides a critical strategic document that underpins the actions and activities to addressing cultural inclusion and awareness for Indigenous peoples within businesses.

RAPs typically provide an organisational commitment to building relationships with First Nations peoples and communities, through actions such as cultural awareness training, participation in events and commitments to employment and procurement targets for the organisation, commonly representing the appropriate proportion of the Indigenous population (3.8%). It follows therefore that Agriculture will need to grow its Indigenous representation by over 2,500 First Nations peoples based on current employment levels on-farm. Equally, organisations who commit to RAPs will need to attract Indigenous talent specifically for their organisation, creating contestation for current and future First Nations people in the sector.

RAPs were recently highlighted by the National Farmers Federation (KPMG, 2023) as a pathway for agriculture to increase Indigenous employment. They note, “Australian agribusinesses have a responsibility to foster an industry underpinned by cultural awareness and inclusion” (KPMG, 2023). There is a long way to go for agriculture, with fewer than 5 agricultural organisations holding an active RAP (Reconciliation Australia, 2023).

Identification and development of Indigenous agricultural businesses Further to the development of RAPs, Indigenous procurement and the development of Indigenous businesses also encourage new pathways for First Nations employment. For example, First Nations businesses are over 100 times more likely to hire Indigenous workers than are non-Indigenous businesses (Supply Nation, 2018).

It is estimated that there are at least 114 Indigenous agribusinesses in Australia, generating $97.2million in revenue and employing 637 people (Barnett et al., 2022). As RAPs encourage Indigenous businesses through procurement targets, substantial increases will be needed to build and nurture Indigenous agribusinesses into the future.

Conclusion

The employment of Indigenous peoples provides agriculture with a rich opportunity - not only by addressing current workforce shortages but by creating social licence and building human resources skills and knowledge in the agricultural sector. Equally, agriculture could play an important role in reducing the unemployment rate of First Nations peoples, while providing ongoing connection to country and upskilling of Indigenous workers to lead and manage the transformation of the substantial Indigenous Estate into profitable, resilient agricultural production.

Agriculture must engage in actions of reconciliation and build strong pathways for Indigenous employment, committing to RAPs, supporting university scholarships, and transforming agricultural media. The sector needs to address legacy impacts of racism and view Indigenous employment as a critical opportunity for the industry to address employment challenges and social licence pressures.

This paper provides an understanding of the historical factors influencing Indigenous participation in the agricultural workforce, the current state of demand for talent generally and the opportunities that present for agriculture to pursue in bolstering the employment of First Nations peoples across the country.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank John Kim, .id (informed decisions), and Dr. Siddharth Shirodkar for providing data and analysis used in this paper.

Please note, the terms Indigenous and First Nations are used interchangeably throughout this paper to refer to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia.

References

Anthony, T. (2004) Labour relations on northern cattle stations: feudal exploitation and accommodation. The Drawing Board: An Australian Review of Public Affairs, 4(3) 117-136.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) “Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians” https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release#:~:text=Media%20releases-,Key%20statistics,under%2015%20years%20of%20age.

Barnett, R., Normyle, A., Doran, B., Vardon, M. (2022) Baseline Study – Agricultural Capacity of the Indigenous Estate. Cooperative Research Centre for Developing Northern Australia. https://www.crcna.com.au/resources/publications/baseline-study-agricultural-capacity-indigenous-estate

Binks, B., Stenekes, N., Kruger, H. and Kancans, R. (2018) “Snapshot of Australia’s Agricultural Workforce” Department of Agriculture and Water Resources ABARES, 3, 1-14.

Brown, C., D’Almada-Remedios, R., Gilbert, J., O’Leary, J., Young, N. (2020) “Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Centring the Work Experiences of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Australians” (Diversity Council Australia/ Jumbunna Institute: Sydney)

Bunbury, B. (2002) “It’s not the money, it’s the land: Aboriginal Stockmen and the Equal Wages Case” (Fremantle Arts Centre Press: Fremantle)

Burney, L. (31 August 2016) Maiden Speech, Parliament of Australia

Charles Sturt University (2023) “First Nations Agriculture Initiative Fund” https://www.csu.edu.au/office/advancement/giving-to-csu/active-funds/indigenous-agriculture-initiative

Commonwealth of Australia (2021) “Closing The Gap- Commonwealth Implementation Plan” https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/commonwealth-implementation-plan-130821.pdf

Davis, R. (2006) “Eight Seconds: Style, performance and crisis in Aboriginal rodeo” (ANU Press: Canberra).

Foster, R. (2000) Rations, coexistence, and the colonisation of Aboriginal labour in the South Australian pastoral industry, 1860-1911. Aboriginal History, 24.

Head, L. (2000) “Second Nature- The History and Implications of Australia as Aboriginal Landscape” (Syracuse University Press: New York)

Host, J. and Milroy, J. (2001) Towards an Aboriginal labour history. Studies in Western Australia History, 22, 3-22

Jobs and Skills Australia (2023) “Recruitment methods used by employers” https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/work/recruitment-methods-used-by-employers

KPMG (2023) “Realising the Opportunity Report”

McGrath A (1987) “Born in the cattle: Aborigines in cattle country” (Allen & Unwin: Sydney)

National Farmers Federation (2019) 2030 Roadmap: Australian Agriculture’s Plan for a $100 Billion Industry. https://nff.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/NFF_Roadmap_2030_FINAL.pdf

Paterson, A. (2005) Hunter-gatherer interactions with sheep and cattle pastoralists from the Australian arid zone. Desert Peoples, 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470774632.CH15

Pratley, J.E. (2019) Indigenous students do not choose agriculture at University. Proceedings of 19th Australian Agronomy Conference, Wagga Wagga. https://acda.edu.au/resources/IndigenousStudentsDoNotChoose AgricultureAtUniversity.pdf

Pratley, J.E., Graham, S., Manser, H., Gilbert, J. (2022) The employer of choice or a sector without a workforce? Farm Policy Journal, 19(2), 32-43

Reconciliation Australia (2022) 2021 RAP Impact Report. https://www.reconciliation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2021-RAP-Impact-Report.pdf

Reconciliation Australia (2023) Who has a RAP? https://www.reconciliation.org.au/reconciliation-action-plans/who-has-a-rap/

Slatter, B. (2023) “Snapshot of Australia’s Agricultural Workforce” Department of Agriculture and Water Resources ABARES Insights, 3, 1-16.

Stead, V and Altman, J (2019) Labour Lines and Colonial Power- Indigenous and Pacific Islander Labour Mobility in Australia. (Australian National University Press: Canberra)

Supply Nation (2018) “Indigenous Business Growth: Working together to realise potential” https://supplynation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Building-Indigenous-Growth-Report.pdf

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)